Interval 1

Interval 1 – The Planet Warms Up

Around 56 million years ago, the Earth’s climate suddenly got much warmer. Over a period of 20,000 years (an instant in geological time) global temperatures increased by around 6 degrees centigrade. This event, which is called the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, seems to have been caused by a massive release of greenhouse gases trapped in the deep ocean.

Dead microorganisms continuously rain down to the ocean floor, at the rate of millions of tons a year. When these plants and animals decay they release methane gas. In the cold, dark, high pressure conditions of the sea bed this gas can get trapped in a cage-like structure of water molecules called a clathrate. These clathrates build up in deposits on the sea bed that are known as methane ice. If the temperature of the sea bed rises past a certain point, the clathrates can melt, releasing billions of tons of methane gas into the atmosphere. It seems that this is what happened at the end of the Paleocene.

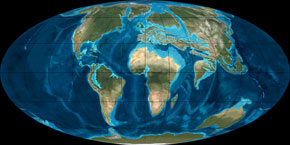

As marine and continental surface temperatures soared, there were huge extinctions of deep sea organisms – in some groups of deep sea microorganisms as many as 50% of species went extinct. But for other groups of organisms, the effects seem to have been positive. Plankton diversified hugely. And on land, there was a dramatic increase in the abundance and diversity of mammals. The warmer temperatures in the northern hemisphere allowed many mammals to migrate from the Old World into North America via routes that would previously have been too cold. Many modern orders of mammals, including artiodactyls and perissodactyls, appeared during this time.

One thing that is notable about this period is that there were few if any large mammals – compared to the Paleocene, body size had decreased dramatically. Some researchers have suggested that this dwarfing effect may be a consequence of increased levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Why is the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum important?

In terms of rate and magnitude the rapid warming of the climate at the end of the Paleocene event is very similar to warming events that we will experience in the near future due to burning fossil fuels. Because of this, studying the climate in this period and its effects on the Earth’s organisms may provide important clues to the long-term effects of global warming. More worryingly, it is possible that rising ocean temperatures today may cause the release of methane from seabed deposits, much as it did 56 million years ago. If this happens, global warming may accelerate beyond anything yet seen. While the Paleocene mammals actually diversified and prospered during the Thermal Maximum, the effect on our species, which is dependent on agriculture for survival, is likely to be devastating.

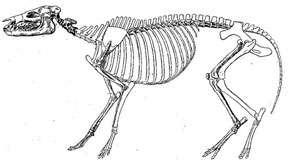

Hyracotherium; an early Eocene perissodactyl

One of the first perissodactyls to appear in the fossil record, Hyracotherium is an early relative of horses and probably quite similar in size and anatomy to the common ancestor of all the perissodactyls. It averaged 2 feet (60 cm) in length and 8 to 9 inches (20 cm) high at the shoulder and had 4 toes on each front foot and 3 toes on each hind foot. The skull was long, with 44 low-crowned teeth adapted to a diet of leaves, fruits and nuts. Specimens of Hyracotherium are abundant in what is now the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming. Today this area is arid desert, but 55 million years ago it was covered in lush rainforest.

Following the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum global temperatures dropped, but the long term trend for the next 10 million years was a warming one – by 45 million years ago, the planet was as warm as it would ever be during the Cenozoic. There was remarkably little variation in temperature from the poles to the equator; the temperature gradient from equator to pole was only half that of today's and the climate of the polar regions was as mild as the modern-day Pacific Northwest. Temperate forests extended right to the poles, while rainy tropical climates extended as far north as 45° - the equivalent of France. This is the time when perissodactyls reached their peak diversity. By the middle Eocene, all the modern groups were present – horses, rhinos, and tapirs – along with many groups that are now extinct – chalicotheres, paleotheres, brontotheres, amynodonts, hyracodonts, and indricotheres. The low crowned teeth of these animals were well-suited to feeding on the soft leaves and fruit of the tropical and subtropical vegetation. The middle Eocene marked the end of the warming trend for the Cenozoic. From then onwards, although global temperatures were to remain comparatively warm for the rest of the Eocene, the planet would begin to cool. The world we live in today is a relative icehouse when compared with the world of 45 million years ago.

Why should we be concerned with climate change?

The average temperature of the planet during the middle Eocene was around 28 degrees centigrade (82F). Today, the average temperature is around 14 degrees centigrade (57F). Scientists estimate that the surface temperature of the Earth has increased by between 0.5 and 1 degree C over the past 100 years and may rise by another 1 to 6 degrees by the end of the 21st Century. Even at this level, global temperatures would be far less than they were during the Eocene. So why should we worry? The answer, of course, is that the rate of change is much, much quicker. The sort of temperature changes we see recorded in the Earth’s geological record took place over millions of years, rather than a few hundred. Most organisms are incapable of adapting to this rate of change and many species are likely to go extinct. The effects on our own species could be particularly devastating – a significant rise in the global climate and resulting changes in weather patterns could make much of the tropical and subtropical regions of the world unsuitable for agriculture, minimally leading to widespread social and economic upheaval and ultimately even widespread starvation.

< Interval 0 | Interval 2 >