Finding

Fieldwork

Fieldwork, involving prospecting for, excavating and collecting fossils, is what most people think of when they hear the word paleontology. Popular culture references to excavation make it seem exciting and glamorous. While it certainly can be thrilling to be the first person to find a fossil that has been buried for millions of years, most excavation is careful, painstaking and often tedious work. This is because the information associated with the specimen is as important as the actual fossil, and fossil collection often is as much about collecting data is it is about collecting specimens.

Like most vertebrate fossils, the remains of perissodactyls occur most commonly as scattered individual bones. These are often broken and abraded before being buried and fossilized. It’s rare to find more than a few bones of any one animal; while complete skeletons are sometimes found, this is exceedingly uncommon. The parts of the animal that are most commonly preserved are the ones that are the hardest and most dense – teeth and the surrounding jaw bones.

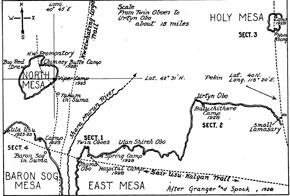

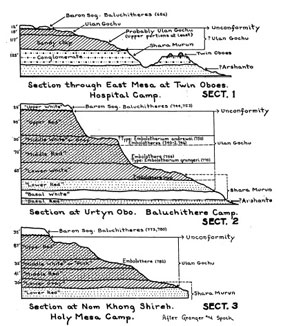

To find the remains of perissodactyls, paleontologists have to start by looking in the right place. The earliest known perissodactyls come from the beginning of the Eocene period, around 55.5 million years ago. Of course, that doesn’t mean that there are no perissodactyl fossils from rocks that are older than this, just that these are the oldest that we have found so far. Fossils tend to occur in sedimentary rocks; because perissodactyls are land animals the best sort of sediments to look in will be ones laid down in freshwater; by rivers, in lakes, or in swamps. Because fossils are exposed by erosion of the surrounding rock, the best places to look are those where a lot of erosion is taking place – riverbanks or cliff faces, for example. Desert areas are often rich hunting grounds for fossils; rock surfaces are not obscured by vegetation and wind-blown sand and dust rapidly weathers away the rock.

Paleontologists don’t just go to an area and start digging; as AMNH paleontologist Roy Chapman Andrews once remarked, “a paleontologist rarely digs for fossils unless he sees them.” Paleontologists spend hours, and often days, walking slowly over likely terrain, sometimes stopping to examine a likely rock exposure more closely. This is called “prospecting.” Fossils are often a slightly different color to the surrounding rock. This will sometimes catch the eye of an experienced collector, even from some distance away. If it turns out to be a fossil, then the real work begins.

A single weathered bone protruding from the surface of the ground may represent the only fossil for miles around, or it may just be the "tip of the iceberg" of a significant find. To discover which is true, the collector has to examine the area carefully. They may need to make some small exploratory digs to discover whether it is connected to other bones. Sometimes the bone may have broken away from the rest of the body after the animal died. The rest of the body may be nearby and also weathering out, or many miles away and still buried under hundreds of feet of rock.

There may be other bones scattered around which come from different animals. The position of these needs to be carefully recorded before any excavation occurs, as well as details of the surrounding geology. Later this will help scientists to work out whether the animals all lived at more or less the same time, and are part of the same ecological community, or whether they lived at different times that are millions of years apart. Even when excavation starts, paleontologists will keep samples of the rock surrounding the fossil (which is called the matrix). These can be used to date the find and may contain microscopic remains of animals, or pollen from plants, that can be used to provide more information about the environment in which the animal lived.

Fossil bones are often very fragile and so excavation is done very slowly and carefully. If the exposed bone is cracked or crumbling, it may need to be treated with adhesives as it is exposed – this is called consolidation. Not all the surrounding rock will be removed; some will be left to provide support and then removed when the fossil has arrived back at the laboratory or museum. The exposed bone and matrix is then covered in layers of bandage or burlap soaked in plaster. This hardens to form a protective cocoon around the fossil, which is known as a field jacket.

Field jackets for large specimens can be weigh hundreds of pounds. In the early days of collecting, teams of horses would used to move them. Today, paleontologists use a variety of ways to extract large jackets, including four-wheel drive trucks and even helicopters. But often it still requires gangs of people to lift and carry jackets to a point where vehicles can reach them.

The exact location of the fossil is recorded using a GPS unit and the coordinates are noted in the collector’s field notes along with as much information as possible about its surroundings. There are several reasons for this. First, paleontologists are often only able to work in the field for a few weeks at a time. At this rate, they may need to return to a site over several years to extract all of the material there, so it is important that they can find the exact location again a year later. Second, as we discussed above, information about the site can be very useful to scientists studying the fossil who want to reconstruct the animal’s habitat and ecology. Finally, by mapping the location of different fossil finds in a particular area, collectors may be able to predict where to go to increase the chance of finding new fossil sites. This is why field notes are so important and why they are usually kept in the museum housing that eventually houses the fossils.